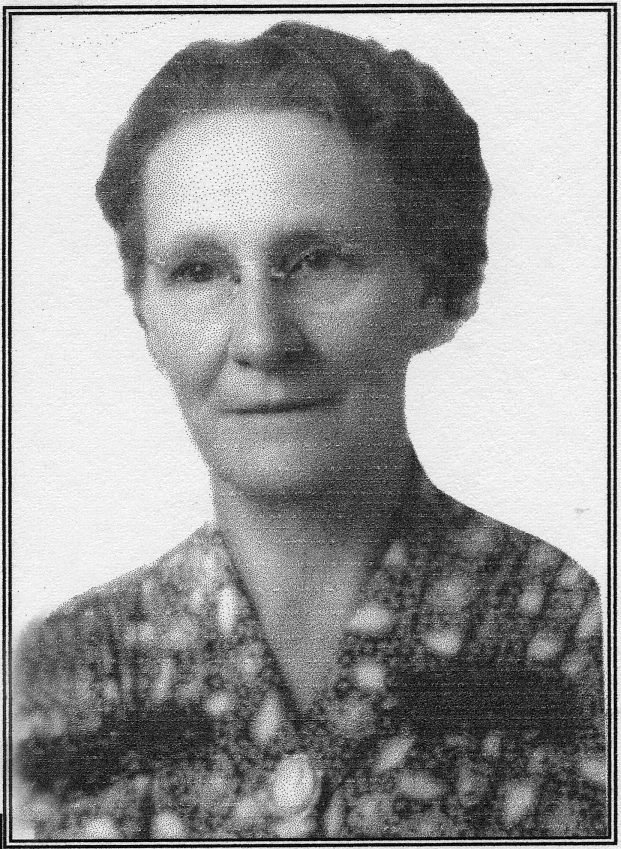

(Mary Elizabeth Tolman Glenn shares her history. Mary is the daughter of Cyrus Ammon Tolman and Maria Louisa Pickett.)

Part One: And so I am to write a story of my life–FROM OUT OF MY MOUNTAIN HOME.

I came into the world with the passing of the ox team, and the tallow dip. I have lived through team and wagon days, and horse and buggy days. I have seen the passing of the first open cars, when we sometimes could boast of traveling twenty miles an hour over a dusty road full of chuck holes. Now we glide smoothly over a paved road and travel 60 and 70 miles an hour and, if we wish to be daring enough, we can fly through the air.

Life is like a telescope, view things from one end and things seem so far distant and remote. They are almost incomprehensible. Viewed from the other end everything comes up close.

To youth, old age seems so far in the dim uncertain future, it is hardly worth thinking about. While youth, as viewed from old age, seems only yesterday. To me it seems only a short time ago that we settled in Idaho, when it was not yet a state. The country was raw and wild. There was danger from Indians. There were a few log dwellings. There were no fences, no schools, and no churches.

What few things could be bought must be hauled a long way by team and wagon. It was up to the people to provide for themselves. They must force the land to yield them a living. I remember the jerked venison, made by cutting the deer meat into strips and dipping it into scalding brine, then hanging it in the sun to dry. To me at that time it was very palatable.

In sickness and accident people had to live or die with what help friends and relatives could give. Any one who was handy at all soon learned to close the eyes of the dying and bind up the vitals of the newly born.

I remember hearing them talk of taking up the rough lumber floor from a house to make the first coffin, and it was not any glittering affair of satin and bronze. But no matter people died and had to be laid away. There is no holiday from emotions. Joys and sorrows go right on regardless of circumstances.

I was born January 7, 1880 in what was then called Rush Valley, about 40 miles out of Tooele City, Utah, to Cyrus Ammon Tolman and Louise Pickett. We came to Idaho when I was two years old. I was too young to remember the trip. But I do remember the Goose Creek Valley when it was quite new and raw.

All of the houses were built of logs very low and with a dirt roof. Most people built two rooms first, then would add a room at the side making it a “T” shape. The roof was made of poles laid close together, then a layer of straw, then dirt. No matter how close together the poles were laid, the dirt trickled through. The houses were lined with unbleached muslin The dirt would trickle through onto the muslin ceiling and make it look baggy. Then when we got very heavy rains, the rain came through so each one of those baggy places were dripping water.

It wasn’t long until someone built a homemade loom to weave carpet. So as fast as people could save rags, they tore them into one inch strips and sewed them together and had them woven into carpet three feet wide, which had to be sewed together with carpet warp. By the time I was ten years old most people had carpet on at least one room. The kitchen was always pine boards, which called for a twice a week down-on-the-knees scrubbing.

One of the spring jobs was to take everything out of one room at a time and whitewash the walls and ceiling. You really do not know what a real nasty job it is until you have whitewashed. In a room where there was carpet, it must come up, then clear out the dirty straw, put in a layer of clean straw, bring in the carpet after it had been well whipped to get the dust out, then came the tug-of-war to get the carpet stretched and tacked down again.

When it was done it was really rewarding. The house was very clean and when we got the curtains up at the windows, pictures on the wall and any other decoration available, the houses become more attractive than you might think.

We had one log building, not very large, with three windows on either side and a door in the end. It was the church, school house, and recreation hall. When they organized a ward they called it the Marion Ward, in honor of Francis Marion Lyman, on of the church authorities. It is very likely that he is the one who organized the ward and ordained the bishop. I remember him being out to conference many times during by younger days. Our church was: Sunday School at 10:00 A.M.; Sacrament Meeting at 2:00 P.M.; and Primary on Saturday afternoon. On special occasions there would be a dance.

I remember going to a dance or two as a child. At that time it was the fashion to wear hoops. All of the younger women wore them. It was always crowded and people must sit very close together, so it made the hoops poke a way out in front. Every woman had a little tent over her knees.

When I became six years old, I went to school in that building. I remember my first school teacher very well. His name was Morgan. He was an Eastern man, just a young man. He could play ball with the boys and when winter came and the water flooded out over a nearby field, how that teacher could skate! He could waltz, cut a figure eight and all sorts of tricks. At recess we played ball, pomp pomp pull-a-way, run and I’ll catch you anyway, hop scotch, tiki, and lots of other things. Kids will have fun regardless of day and age or circumstances. The school was not graded as they are now days. The school work was grouped according to the various readers. First, it was the A B C class, then the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth readers. I still have my old fifth reader. The pieces in it are masterpieces. Later it was used as a text book for the education class at the Albion State Normal, but just the same we wrestled with it in our little one-roomed school house with one teacher for 100 pupils. I don’t know whether I learned anything or not, as we never had examinations. We just went to school and it was up to us to learn what we could.

The main characteristic of the country was Goose Creek which wound its way down the middle of the Valley. In the spring during high water it was stream enough to drowned a person. When the snow was going off it often flooded over its banks, so there was a wide strip of willows and underbrush on either side. During the summer the water was only a little trickle, so that in places we could play up and down the bottom of the creek bed. Where the creek made a sharp turn there would be a deep hole. These places made small swimming holes. My brother George, two years my junior, and I, along with my cousins and other children roamed up and down that creek looking into bird’s nests, gathering wild roses and yellow currants, wild gooseberries and strawberries; all of them so sour we would make a wry face to even taste them, but we gathered them anyway. The underbrush harbored various kinds of varmints; skunks, badgers, porcupines, even wild cats and the surrounding sagebrush was full of coyotes. It was hard to keep chickens or the varmints would catch them. The wild cats even killed the domestic cats. We would set traps on the various trails to catch the coyotes and wild cats.

In the summertime when we had traps set, we would look out first thing when we got up to see if the bushes were waving. If they were, we knew there was something in the traps. One time we were gone for the afternoon, and when we got home the bushes were waving. My brother and I slipped up close where we could peep through the bushes and there was a hen in one trap and a wild cat in the other. Evidently the hen got caught first and the wild cat thought it would make a nice meal, but before he got very far along with his meal he got caught in the other trap. We went for an older cousin who lived near. He came with his gun and as he got near enough to shoot, the wild cat opened his mouth very wide and spit at us. My cousin shot right down his throat.

The funniest thing about our trapping happened the summer I was nine years old. My brother George was seven and we had a cousin from Tooele, Utah out visiting for the summer. She was fourteen years old, but she was very small for her age and I was large for my age, so we did not seem so far apart in age. Anyway, she liked to roam up and down the creek with us and one day as we came to where we had traps set, what did we find, but a skunk. We felt that the three of us could handle the situation ourselves, the only question was how. The only weapons at our command were rocks in the creek bed. We decided rocks it would have to be. Back and forth we went carrying rocks as large as we figured we could throw effectively, until we had quite an arsenal. We decided to take it in relays, one would run up and throw a rock and then another. That seemed fine until we tried it. Then we found the skunk had ideas of his own. By the time we got close enough to hit him, he threw off such a terrible odor we could not stand it. So we went into a huddle. There was a lot of young sagebrush nearby, which was very pungent in its own right. We found that if we held that close to our nose it offset the smell of the skunk to quite an extent. So with our left hand holding a rock, we began the rounds.

We killed the skunk all right, but when we got home, our folks didn’t know whether to own us or not. I have heard it said that the only way to get rid of clothes full of skunk odor was to bury them along with the skunk I think our folks felt like burying us, clothes and all. But they managed someway to salvage us kids.

Compared to the way children go and do and see now days our lives were dull and humdrum. We seldom went anywhere except to our church meetings and school. School from three to four months during fall and winter. Once or twice it lasted six months and that seemed ages.

We suffered hardships and privations. Our food wasn’t adequate, neither was our clothing. Our beds were cotton ticks stuffed with straw. During the cold weather we had to crowd as many as possible into one bed because there wasn’t enough covers to make more beds. I never remember being hungry nor when there wasn’t anything to eat, but if children now days had to sit down to our fare they would think they were starving.

Our clothes were mostly homemade. We could always buy shoes and sometimes coats. The other things were up to our mothers to make. There were no snug fitting underwear, just what mothers could make from cotton cloth. My mother was expert with needle and thread so my clothes were well put together, but not always warm Our feet suffered most. If there were such things as children’s overshoes, they never came to our country. It was not unusual to see men with their feet wrapped in grain sacks. However, the shoes were stronger and sturdier than they are today. Shoes were made of genuine cowhide and as near water proof as it was possible for them to be.

We went to school through snow or mud, whichever the weather dished out, our only salvation was hand knit woolen stockings. Nevertheless our feet got frosted. When it was extremely cold we had chill blains that itched and burned enough to drive us nuts. Sometimes they were so sore we could hardly wear our shoes. In spite of it all children grew up, perhaps I could say those who couldn’t grow up died. When people can’t have greater things they learn to enjoy lesser things.

One thing that stands out in memories was our July celebrations. We would combine the 4th and 24th of July celebrations. Sometimes the big doings were on one date and other times on the other, but it was always a hay day. Sometimes it was a string of wagons going over the desert to Cotton Wood where there was a large grove of trees. Other times we went to Oakley. There they would build a bowery where the programs would be. By the time I was ten years old Oakley had a brass band. We would have patriotic music, songs, and speeches. The girls were all out in white dresses with red, pink or blue ribbons flying. There would be flags and bunting everywhere. It was really an enthusiastic day. We children caught the spirit and thought our nation was the greatest in the world and the Fourth the greatest day ever. It is something lost to children of today, which makes a loss to the nation. No one could ever have talked Communism to us. It was also a day of treats for which we must save our nickels. The stores got fire crackers and other noise makers; also tiny flags, extra candy and pressed popcorn. We even had+ ice cream, really something in our day. That meant the older boys had to take a team and wagon into the mountains as far as there was a road. There they would camp over night. The next day they rode the horses a ways farther into the hills until they found snow. They would fill grain sacks with snow and bring all they could on the horse’s back to the wagon. The next day they would drive home. All that trouble so we could have some frozen custard, but what a treat it was!

We all rode horses. If there was nothing better, we rode the work horses with a saddle, if we had one. If not we rode bareback. Girls must be ladylike and ride sideways, so we would tie a rope around the horse to hold on to, but we could ride on the horse holding onto that rope. When I was ten and eleven years old, everyone turned their milk cows out on the desert west of Marion where there was green feed in the spring. It was often my job to ride out and get our cows.

At that time we had an old horse which had been a cowboy’s horse. I also had a man’s saddle. When I came where people could see me I slipped my knee over the horn of the saddle so both feet came on the one side of the horse, but one on the desert, I rode boy style. When I came to the cattle I would let the old horse know which cow I wanted then it was up to me to stay in the saddle, he would do the rest. If the cow dodged he would dodge also and get around her with such a jerk I had to hold onto the saddle for dear life. When one cow decided she might as well go on home we would repeat the process until I had them all, usually three or four. Then the old horse would follow them leisurely home. I rode another horse that was worth mentioning.

When I was about thirteen years old we came in possession of a little buckskin mare, who in her hay day had been on the race track. Her race track name was Penny Weight. About the same time I became the owner of a lady’s sidesaddle, which also had seen its best days, but when I got that sidesaddle on Penny Weight’s back and myself perched in it I felt like I was going places. Sometimes I really did for while Penny Weight was an old horse she had not forgotten her race track training and once on the road, if she could see a horse ahead of her she would pass it come what may. She never would let herself be disgraced by letting any of those farm plugs pass her, so there were times when she really left the road behind her. She also had a mind of her own.

One day I had been riding some and came home for something, intending to go again, but I soon found Penny Weight had ideas of her own about that. She didn’t want to go. When I tried to make her go, she reared straight in the air. I had presence of mind enough to grab her mane and hold myself close to her neck, but it seemed an interminable time before she decided to bring those little front hoofs down to earth. I had several near accidents and as I look back I wonder how I ever came through without breaking my neck. It must have been pure luck. There were some boys and girls who did not only get their necks broken, but were banged to pulp. Now I am scared to death of horses.

When I was seventeen years old I had two girl friends about the same age. My brother and their brother, both fifteen, all decided we wanted to see the Shoshone Falls. The only way to get there was with a team and wagon, but we were all used to handling horses so that was no problem. After some discussion and planning, we started. The wagon was quite full with five of us, food for three days, bedding for ourselves and hay and grain for the horses. It took us all day to make the drive. There was no grade (road) like there is now. We entered the canyon right by that pond that is there now. The road came down about where the water falls into the pond is. It looked to me like it was straight down. We locked the wagon wheels so they could not turn at all and then the horses had to hold the wagon back. I thought surely the wagon would pitch right over the horses. We camped there where the pond is. The next day we spent exploring the falls and everything there about. We crossed on the ferryboat and explored the other side. It was in June when the water was the highest and that was in the days when the water went down the river. It really was a wicked stream. We could hear the roaring of the falls for miles before we got there. The ferry crossed just above the falls. In midstream the current was very swift. It pulled on the boat until it made the pulleys grind on the big cable. The sight of those awful falls just below us was not comforting. Even my teenage judgment told me that if anything gave way we would take a very quick ride over the brink. But nothing gave way and we made it over and back. We held onto the cable and climbed the bank down below the falls to the water’s edge. The spray fell on us and waves slapped us until we looked as if we had been dipped in the river. We walked wet planks and climbed over slippery rock until it is a wonder we were all in that wagon when it went home. But to use a trite saying, a good time was had by all.

When I was about seven years old, my mother went to Salt Lake City and took tailoring, so she did the difficult sewing for most of the people round about. She even made men’s suits of clothes. She was often sewing woolen cloth so every seam must be pressed, which called for a hot iron, which wasn’t easy to have in the summertime. So it fell to me to go to the wood pile, get a pan of chips, then take off the stove lid and make a pint-sized fire on the grate, then set the iron right on the fire to get hot. I had to do that so much it irked me very much, but I watched my mother press seams, hems, and plackets so many times that when I came to sew myself, I could just see how those things should be dome, so it was a blessing in disguise. My grandmother told us it was worse when she was a little girl as they didn’t have matches. If the fire went out they had to borrow some. She said she often took an iron pot and walked to the neighbors to bring back some live coals buried in ashes so they wouldn’t go out. So even though it was bad, it could have been worse.

By the time I was sixteen, I was making most of my own dresses. Up until then we had not been able to buy paper patterns, but one day I had a magazine, not a slick one like we have now days, it was printed just like a newspaper. But there were pictures about an inch high of paper patterns to be had for ten cents each. I picked one out and sent my dime and in due time it came. I was used to full skirts but they were all gathered in at the top, but here was a pattern of a new kind. At sixteen I was old enough to wear long dresses, so I startled the natives by coming out in a skirt which measured six yards around the bottom, twenty five inches around the top and not a gather in it!

The winter I was nineteen I was asked to relieve the school teacher a little by hearing some of the younger ones recite their lessons, along with taking lessons myself. For the help I received $12 per month. As we had only five months of school it was through by March 1, so there was time for me to attend the Albion State Normal for the spring term. I figured that was the best way to spend my money, because at that time I had a hazy idea that if by some unknown means I could get the necessary education I would become a school teacher. So to school I went. While I did not realize it at the time, I was leaving my childhood haunts forever. I was never to go back, only as a visitor.

Part Three: And to continue my story-THIS IS WHERE A PERSON’S LIFE REALLY BEGINS.

I have always been a little adverse to writing a story of any life, because it takes interesting people to live interesting lives, and I never classified myself along with the interesting people.

My life could be summed up in one sentence, “I have worked in the kitchen.” But then,

We can live without wealth,

We can live without books;

But show me the man

Who can live without cooks.

So, perhaps the kitchen is an important place after all.

There is one nice thing about writing an autobiography,

You need not write a lot.

Of the things you would rather not.

Your memory can take a graceful flop!

Now to get back to my story.

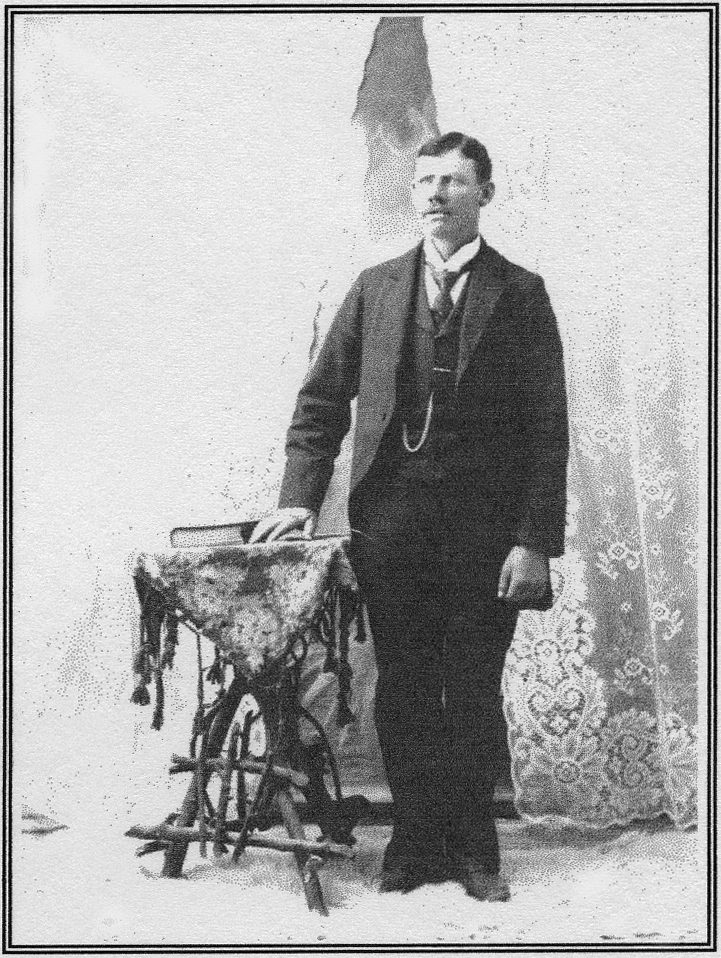

When the school was out at Albion, Idaho, I hired out for the summer to work for some people who lived on Cassia Creek, farther east. These people had a hired man named Andrew Glenn. We stayed there all summer and didn’t even get acquainted. But found friendship in the fall which ended in marriage, March 2, 1900. The distances in that county are long when you must go with a team and wagon. More than that there was nothing to go to. So we never had a date, not even to a picture show, which didn’t exist at that time. We had to be content with walks in the moonlight.

This all happened during the summer and fall of 1899. That winter Andrew took a job driving stage which carried the mail and some passengers between Albion and Kelton, Utah. I went to Logan to visit some cousins who were going to school there. So I was in Logan, Utah when the century turned over from 1899 to 1900.

It seemed quite a mouthful to say nineteen hundred. I thought we would never get used to saying that, but time wore the sharp edges off so it didn’t seem to hard.

I came back from Logan in February. When Andrew and I met again we decided to get married. As spring was coming it would soon be necessary to make adjustments for summer work, so we decided the time was now. We were married March 2, 1900. We did not have a fancy wedding and we didn’t go to the temple. We just got married.

There was a peculiar angle to the childhood background of both of us. Andrew went out in the world for himself at the early age of 12 years. He worked with cattlemen and sheepmen. During the winter often feeding stock for his board. Often he did not have sufficient food and never sufficient clothing or bedding. He worked hard, and suffered cold and privations that a less hardy boy would not have lived through. His work took him far from school or church environment. So he grew up with very little education and no spiritual training at all. At that time the church officials did not contact the teenagers and try to keep them working and teach them as they do now.

My background was different from Andrew’s, but just as peculiar. My father left the church before I was eight years old. He would never consent to my brother and I being baptized. So we came into the church later on our own responsibility. I was baptized in January 1900 while I was in Logan. When we were married my church membership was less than two months old. These unpleasant circumstances broke up the family and created hardships and heartaches. With these few essential facts, I will let that matter rest. My memory takes a graceful flop.

When Andrew was old enough to get a man’s wages, his thrifty nature came out. He began saving his wages and soon had three hundred dollars. The boy friend wanted to get married and was looking for a place to make a home. While he was up at Rigby visiting his sister he found 160 acres of land for sale, three miles east of Rigby. It would take $600 to buy the land and he had only $300 so he persuaded Andrew to use his $300 and buy one 80 acres and he would buy the other. That is how we came to have 80 acres of land a way up there.

So when we were married Andrew bought a team and wagon, and we started out, going that far we would drive the horses only on the walk, so it took us five days to make the trip. That was our honeymoon trip. Between Pocatello and Idaho Falls we saw nothing but Indians and Indian tepees, as that was the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. We could see Blackfoot over to the east, but that was all. We arrived at the friend’s house March 20, 1900. One man there had logs for sale and we bought enough for one room.

When we got that build the next thing was to clear the sagebrush from some of the land. The brush was small enough to be railed off. That was done by hitching a team of horses on either end of a rail, such as the train runs on. After the brush was railed it was raked into ricks and burned. I went out lots of days with a pitch fork and carried a burning bush from one rick to another. We managed to get in quite a patch of grain and some potatoes.

It was very different farming than Andrew had been used to and he didn’t like it. When fall came he sold the crop, then sold the land back to the man who owned it in the first place. The man paid him $600 for the price they had paid for the whole 160 acres.

So we were headed back to Cassia County. When we got to Raft River we were told that there was a place for sale on the Sublett Creek, 10 miles east of Malta. Andrew went up there and bought that. He paid $800 down on it and got three years time on the balance. To me that $1200 looked like that many white elephants. I had never heard of people like us owing so much money. But we made it in the three years time.

On Sublett Creek there was plenty of land and it was very good land, but the water was the problem. It was one continual scrap over water. It is up in a mountain gap, quite high, so it was cold most of the year.

There were only sixteen homes on the creek, so you can see there was not much social life there. There was a one room school house. Less that half of the people were LDS and some of them not very active church workers. So all we tried to have was a little Sunday School, it you could stretch your imagination enough to call it that. We never did feel that we wanted to stay there all our lives.

We farmed there for four years, raising hay and grain. We could have raised potatoes, but there was no sale for them. Wendell and Wesley came to live with us while we lived there. They were born at Marion, but spent their baby days at Sublett.

In February 1906 we sold the farm and moved again. We had heard lots about Emmett, Idaho. It was a place where they had plenty of water and it was warm. Also they raised lots of nice fruit. That was the three things we longed for at Sublett. So we thought that would be the heaven on earth.

We went there and bought a place and farmed there the summers of 1906 and 1907. We soon found that there were things there we didn’t like. Along with plenty of water there were plenty of mosquitoes. Along with what we had thought were advantages of heaven we also found the tortures of hell. The mosquitoes were so thick in the evening we could hardly breathe. And in spite of screens at the windows and doors, enough would get inside to continue their business at night.

As for the farming, it wouldn’t have been possible for us to understand that there could be such poor ground. There were spots where fruit trees would grow. The rest of the land was so poor you couldn’t even raise a disturbance on it. We decided to sell again the very first chance that came along.

The chance came the fall of 1907. We sold the place for more money than we paid for it so we came out all right. We heard that the man who bought us out sold for still more, but why I will never know. Thelma came to live with us while we lived at Emmett. Our trip to Emmett and back was on the train. When people there asked where we were going now, I said, “back to old Cassia, and this time to stay!” I said if we ever left again we would go to Blackfoot where crazy people belong.

Benjamin Franklin said three moves was bad as a burn out. This would be our three moves, so it must be our last.

So back we came to Cassia county, which at that time took in Twin Falls County. We bought our present west 40 acres that winter, but there was no place to live, so we stayed at Marion that winter. Andrew came down and built a lumber shack in the sagebrush for us to live in. He bought a team and wagon in Marion. We had some things we had shipped on the train, so as soon as the weather would permit, we moved down. We arrived here March 20, 1908.

We were confronted with another sagebrush clearing job. The brush here was too big to be pulled out with a rail. It was cut with a V shaped grubber pulled by four horses. We hired that done. Then once more we went through the raking and burning.

Our life here that spring would be hard to describe. It was a cold spring with a lot of hard wind. The dirt flew in clouds, sometimes we could hardly see. I would have to wash a dish before I could use it, and our clothes and bedding was almost dirt itself. I sometimes wondered if I could possibly take it any longer, but it is surprising what a person can endure when they can’t help themselves.

When July heat finally go here, it still wasn’t pleasant in the lumber shack. Along with trying to raise some crop we built a house that summer and moved into it in September. Calvin came to live with us in October 1908. Farming wasn’t any joke then either. Trying to set water in the loose ground without sod or anything to help check it, it was almost impossible. When the crop did get green the jack rabbits came in on it. Our field was a little oasis in the forest of sagebrush. The rabbits came in by the hundreds. About all we did that year was get some hay started and raised some potatoes and other garden produce to help us keep eating.

The spring of 1909 Andrew bought posts enough to go around the 40 acres, and he bought wire netting and fenced the field. The rabbits were expert at jumping over the fence and digging under. At best, all we could do was check them some. Our crop was slim again.

The spring of 1910 other people began taking the sage brush off. This relieved the rabbit situation some. By that time our finances were really down to bedrock. With buying the land and the water rights, building the house and buying what we must have in farm implements, the money we brought with us was all gone. This section was school land, so it was bought from the State of Idaho. Then we must buy the water right from the Twin Falls Land and Water Company. We were still making payments to the State and the water right had to be paid out about that time. I don’t remember which year we finished that. We were really hard up. Andrew went across the country and stacked and drove the school wagon one year. He did everything he could to make ends meet.

Time never stands still for any man, or their troubles either. The years went by and finally we came out on top.

Wendell started school the fall of 1908. He had to walk 3/4 of a mile through the sagebrush and catch the school wagon at the intersection one mile north of Kimberly. He didn’t like to do that all by himself, but it had to be done. Wendell didn’t go to the old lumber school house which stood just east of where the new LDS Church now stands. They were just starting to hold school in the new brick school house when he started. They were building in the second block off main street, in the block just west of the Kimberly park.

Now it is about time to say something of our church activities because it was in Kimberly that our church work really began. There wasn’t enough church at Sublett to do anything for anyone.

There was a ward at Emmett, but the people came from all around the country. We didn’t get to well acquainted or work in the church at all. But it was there that Andrew was ordained to the office of an Elder, by Bishop David Nelson. Our stake headquarters was at Union, Oregon, so we didn’t get to conference or anything like that. The stake officers came to visit Emmett once while we were there.

Boise and all of the country between Hagerman and Emmett was still in the mission field. Hagerman was a branch of the Marion Ward when I was young. People would say, “Why we can even raise peanuts in the Marion ward,” but it was at Hagerman. When they organized here, Kimberly became a branch of the Marion Ward. So when we came here we were under Bishop Adam Smith, the man who was Bishop here all of my childhood days. He would tell the people here that I was one of his girls. The branch president was Labon D. Morrill. Brother George Hollioke was Sunday School Superintendent. The ward was organized May 10, 1909 with Brother E. B. Wilkins as bishop.

We went to church quite regularly and as soon as I took part in the Sunday School class they wanted me to be teacher. I was simply astounded. I said, “How could I teach people our religion when I didn’t know it myself?” Anyway into the swim I went and I am still there. One man said they didn’t select people for jobs because they knew everything, but they did expect them to learn a few things. So I made my dive into the ocean of knowledge, and I have surely learned a lot. There have been times when I was teaching a class in Relief Society and Mutual as well as Sunday School. But as the family increased there came a time when I could not get out to many meetings. There were so many of us and so many little ones, it was all I could do to keep things going at home and get the others off. But when I began again I found the teaching still to be done.

During the years between 1909 and 1918 special events were concerning our finances and the increase in the family.

Our resources expanded to the extent of buying the east 40 acres. By that time it was the only a patch of sagebrush around us. It was owned by a man named Morris Sommer, a Jew who lived in Boise. We got a bright idea and wrote to him and asked him if he would let us farm the 40 for one year for clearing the brush off. He wrote us he would rent it but would rather sell it. We signed a contract and cleared it in 1913, and farmed it in 1914. That fall we managed to buy it. All of our business with this Jewish man went off without a hitch of any kind, although it was all by correspondence.

About that time a cousin of mine, Myrtle Pickett, of Murtaugh, married a man named Lew Rolins. They moved to Boise and became acquainted with this Jewish man. As soon as Mr. Sommers learned they were from this county, he asked if they knew a man named Andrew Glenn. Lew told him he not only knew him but their wives were cousins. Mr. Sommers said, “Well he is the finest man to do business with that I ever had dealing with.” Lew said, “Well he said the same thing about you.” It was a case of two men having a very high opinion of each other even though they never met.

Now about the family: Kimber came to live with us in 1910 and Fern in December 1912. That winter brought us some trouble. It was a very hard winter and the county was full of sickness. Our children took down one after another as though we had some contagious illness, and Fern developed pneumonia when she was just five weeks old. We almost lost her.

There were several deaths around from pneumonia and one of them came nearly being in our house. Fern has never been as strong as the others and at first I thought her weakness was a hangover from the pneumonia, but now I have changed my line of thinking. I think it was her weakness that caused her to take the pneumonia and the others to get by with a bad cold.

Ada came to live with us in 1914 and Ina June in 1916.

The spring of 1918 brought some different developments. There was a vacancy in the ward bishopric. In February 1918 President Jack came down from Oakley to fill the vacancy. He called Andrew to the position. That made it very necessary that we go to the temple. Something we had talked of many times, but for many reasons we had never gone. In April 1918 we took the eight children and went to the temple.

Elzina came to live with us in July 1918. The next summer 1919 brought us real trouble. Little June took the cholera-infantum. On August 28, the day before her third birthday, she was deathly sick from the start. She suffered terribly and died September 5, 1919. I thought I could never get over it. Her suffering haunted me as much as her death. Anyone who has never watched a person suffer so, and not be able to do a thing for them, can’t imagine what it is. This may be a good time to say a word about cholera-infantum, which is a deadly form of dysentery.

It used to be a common thing for a whole community to be affected in August and September. I read a piece once which said those two months used to be considered the deadly months, until medical knowledge and sanitation did away with it. Then March was considered the worst month because of pneumonia. Now days the doctors can combat pneumonia pretty well.

The next important event came the fall of 1920 when Wendell was called on a mission. He spent the next two years and one more winter in the Southern States. Later Wesley went on a mission to Australia, just as far away as he could possibly go and yet remain on earth. Wendell’s mission cost us $1200 and Wesley’s cost $2000. That is not what the Kimberly ward donated. So far as money was concerned we could not afford it, but we did it anyway.

About that time Thelma went to Salt Lake City and entered the LDS Hospital Training School for nurses.

From 1920 to 1930 I was president of the Relief Society. As well as trying to hold meetings every week, we Relief Society officers helped care for the sick and helped lay out the dead. Hospitals and undertakers were not everyday equipment at that time. We always made all of the clothing that went n the dead, which I felt was quite a responsibility in itself.

So with working hard, trying to carry on our church duties, and going through some very serious financial difficulties, we came to 1931.

On November 6, 1931 our youngest boy, Burton John, born July 27, 1921 was struck with a car as he stepped off the school bus and was killed. So for the second time our lives were darkened by the shadow of a little casket. His death was just opposite to June’s. We watched her die by inches, Burton was snatched away in an instant. Which one is the worst I cannot say, that is another when it is best for the memory to lapse.

It was just over two years when the shadow of the big casket came over our house. Andrew was in Twin Falls and stepped out of his car right in front of another car. He was taken to the hospital where he died November 17, 1933.

When Burton died, Thelma was through her training and was working at the Twin Falls County Hospital. Fern was attending the University at Pocatello. Calvin was in Central America with the U.S. Marines. Fern came home but we did not send for Calvin. It wasn’t possible for him to come.

When Andrew died Thelma was still at the Twin Falls County Hospital. Fern was teaching school near Marion. Ada was in Salt Lake City taking nurses training and Calvin was stationed at San Diego, California. He came home that time so the family was all there.

It took a little time for me to realize that I must continue life’s journey alone. But I have always found plenty to do. I have done a little more traveling later in years, something I always longed to do. I have had several visits to Salt Lake City while Thelma and Ada lived there. I had several trips to Portland, Oregon, when Fern lived there. While in Oregon Fern and I spent three weeks at the ocean side. I have had trips to San Francisco when Thelma and Fern were living there. Then I had one real trip, I spent two weeks touring the eastern part of the United States. I visited Niagara Falls, the Hill Cumorah, New York City, Washington D.C., Mount Vernon, Arlington Cemetery, Robert E. Lee home and several other interesting places. I traveled with a party from Salt Lake City.

Now at the age of 76 I am teaching a class in Relief Society and teaching the adult class in Sunday School. I have some physical infirmities, but as I learn of the condition of some older people, I am thankful my infirmities are not mental.

As I look at my life in retrospect I can see many mistakes we made, many times when we should nave done better. Yet, on the other hand, I am amazed at what we do. I would hate to undertake it again.

If we could view our lives in the beginning as we can at the end we would all have heart failure.

I sometimes wonder how we ever got the work done, both inside and outside. There was not the machinery to help in the field then like there is now. So until the boys got big enough to do a man’s work we had to have harvest hands. Which made extra men to cook for as well as the family to do for. Then later in the fall it was threshers several times in a fall, with grain, beans, and clover seed to thresh.

One fall we had 40 acres of clover seed, and I cooked for threshers for eight days. In preparing for the job, Andrew bought a few old ewes from a neighbor. He would butcher one every evening and let it hang out in the cool air all night. I would fry what I could for breakfast, from the front quarters, roast the hind quarters for dinner and stew from what was left for supper. Just a sample of what it took to feed 17 men. All of this with a baby coming along every two years, left no time to loaf.

There was a time when I would be getting breakfast, packing lunches and seeing that four of five kids were washed, combed and made presentable enough for school. At the same time there was a baby to care for, perhaps two little ones to dress, and twenty gallons of milk coming into care for. Although I did not put the milk through the separator, the boys did that. When they were all off to school, I would wash the breakfast dishes and milk separator and all of those buckets and 10 gallon cans.

I didn’t have any hot water taps, or even running water. All the mechanical help I had was a hand turned washing machine.

And now I am approaching the time in life when no one can tell how soon it will be my turn to say farewell. I will leave this world with faith in God and an abiding trust that we will meet again somewhere, sometime, we must. I have written quite a lingo, and as I write I can’t help wondering how long it may last and who in future generations may read it.

Indeed,

We shoot an arrow in the air,

And it will fall we know not where.

If anyone reads this and thinks it never should have been written, they can blame my granddaughter, Patricia (Patty) Ann Glenn Bates. It is all her fault, but I love her just the same.

Mary Elizabeth Tolman Glenn

January 21, 1956

Mary Elizabeth Tolman Glenn passed way on December 27, 1967 in Murtaugh, Twin Falls, Idaho at the age of 87.