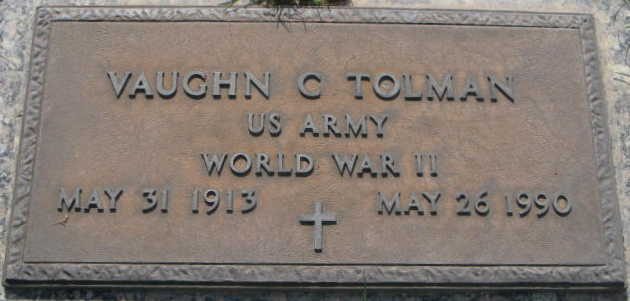

CYRIL LAVON (Vaughn) TOLMAN

31 May 1913 – 26 May 1990

Son of James Milton Tolman & Karen Margrette Ericksen

by Myra Tolman Anderson

At the time of Vaughn’s birth our father was building a house on our dry farm outside of town. We lived in Fairview, Wyoming, just across from the LDS Chapel and when Vaughn was four or five months old, we moved to the dry farm.

I was the only one at home besides Mother and Velma, who was not quite two years old as she was born in October of 1911, and Vaughn in May 1913. Father had taken all of the children to Afton to a celebration and he got home toward evening. Beatrice was working in Afton at the time.

About noon Mother became ill and I ran to the neighbors to phone for the doctor, who lived in Afton five miles away. When he came he told me to get at least three women to help. He was very worried about Mother and was afraid she might not live this, being her 14th child. I was only able to get two women to come as most of our neighbors had gone to the celebration. After the women came, I took Velma in my arms out to a swing under a shed at the back of the house and held her on my lap. I was so frightened. I prayed to my Heavenly Father as I had never prayed so earnestly before. As I finished a voice inside seemed to say to me, “Your Mother will Live.” It was a wonderful testimony to me. One of the women came to tell me to come in. It seemed like hours but, of course, was not more than an hour. The doctor had to use instruments and the baby’s head was very bruised and one of his little eyes was out on his cheek but the doctor put it back in the socket. He thought that Vaughn would live but that Mother shouldn’t try to nurse him.

They had such a bad time finding cows milk that would agree with him, but finally they found milk and he was fine. None of our cows’ milk would do, but Aunt Mattie and Uncle Emery had one that gave milk that agreed with him. There was no prepared baby food then.

My Early Life

I don’t remember much about Star Valley where I was born, but my family tells some stories. I guess milk didn’t agree with me when I was little and one of the things they did to help me was to put lime in my milk, which was Laura’s job, and at each meal she would go out and get some lime. Also there was a time when Mother was out chopping wood and the ax caught on the clothes line and bounced back hitting her on the forehead. It knocked her out for some time.

My sister, Laura, tells of trips to Utah. These trips were slow but chores didn’t stop just because we were traveling. Meat was needed so Dad and the boys would kill a sheep and Mother would cut the fat off and put the meat in a burlap bag that hung in the shade while the meat aged. Mother would then take the fat and rend it down to be used in soap making. The fumes were dangerous so the soap was always made out in the open. We used this soap for everything: laundry, dishes, bathing, and hair. Mom would wash our hair with the soap and then would steep sage tea and comb it through our hair to keep the color even.

I do remember one story. It happened at the old two story house, or cabin, we had on the dry farm. I remember being upstairs with my sisters and the boys was down there killin’ a mad dog, a big black one. It was a strange dog that came around. Mother got us kids, Laura and the whole bunch, right upstairs and we was watching the boys down there getting’rid of that dog. I remember Fos and Hap, I think it was both, had clubs and they finally killed him but we was scared to death. He had froth all over him. He was rabid. I guess, they never had a gun but they killed him with clubs.

I didn’t like being the baby in the family very good. And, boy, the first time I seen a baby why I remember sayin’ “There now, that’s a baby. I ain’t a baby no more.” It was a little bit of a thing. I sure didn’t like being called the baby, but here I am 62, and they still call me, “Baby Vaughn.”

When I was five, my family and I moved to Salem, Utah, from Fairview. The most important thing that I remember about the trip was when Dad came across a guy in a big wagon that was stuck in a mud hole. Dad hooked his team on and pulled the wagon out and that fellow gave him a big crate of fresh cherries—big black ones! Each one of us got a basket. Man, they turned me loose on a full basket and that was the biggest treat I ever had in my life.

When we got down here to the pond (Salem), the first thing I remember was hearin’ some kids taking the Lord’s name in vain. One of them kids had got pushed off a horse. We’d never heard swearin’. We said, “Mother, Dad, did you hear that? You said these kids from Utah was good Mormons!” We’d been taught better than that over there in Wyoming. We always mentioned that too, for quite a while after that.

We got here in July or August. It was right in when the tomatoes was ripe. I remember havin’ all the fresh fruit—watermelons and stuff. Boy, that was good.

I just loved to swim. I swum down in the pond when I was small. Just dived in for the heck of it. Old Albert Peterson bet me $10 one time so I just dove in down there. But, of course, I loved to swim.

Fishing—now that’s my hobby!!! I started to fish when I was about six years old. I couldn’t catch ‘em like Hap and Fritz and them older brothers ‘cause I was too little but I learned as I went. Time I got 8 or 9 years old I could swim and fish right good. Hell, they was all good fishers. Fishin’ is my favorite thing to do now.

When I was 12 years old, Ross Nuttel was there at the head of the Salem Pond. There was one bass about 15” long and about 3” thick that weighed about seven pounds and two others near it that weighed about three and a half pounds each.

Ross said, “Can you catch me a fish?”

I said, “Yah, which one do you want?”

He said, “I want that big one.”

We used them old cane poles then and I always catch ‘em with darning needles (dragon flies). So I throwed my line out there and it hit right next to the big one I wanted. It scared him so he went away and here come those two little ones. I just pulled the line a little and it scared them, too, and they ran out. Then here come that big one back and swallered the fly. I waited until he got her down good and pulled him out. Boy, that was the start of my reputation since he told the whole town.

He’d say, “By darn, ya know, he can’t only catch all the fish in the pond but he just tells ya which one he’s gonna catch and then he does it.”

I had an experience with black magic when I was 12 or 13. It started when me and Chris Horrocks was goin’ to hunt ducks. We got on the horse, Ol’ Babe, and we went down to Grimes’. We was usin’ the new bridle that Roy, Chris’ older brother, had just bought and we tied the mare up to the fence while we was huntin’. We went over and jumped some ducks on the pond and got 3 or 4 and returned in an hour or so. The mare was standing out there and no bridle. It was gone and the mare hadn’t broken the reins or anything.

There was a kid in the meadows so we went over to talk to him. He told us that he hadn’t seen or heard anything. He’d been huntin’ the whole time and when he saw the mare, it was already away from the fence.

He said, “If you want to know who took that bridle, we can go home to Dad and he can tell you who took that bridle.”

We thought it sounded strange but then we said, “Ok.” They lived in an old grainery office over near the dugway. It was like livin’ in a barn. They had their bed pushed back in and there was a little, old pot-bellied stove with a top to cook on.

The kid said, “Dad these two boys had their mare tied with a brand new bridle and someone turned her loose and stole the bridle.”

The man said, “Oh, I think I can tell them who did it.” Then he turned and went into the granary. I don’t remember the mumble jumble now but he just crossed his hands over his forehead and pretty quick he took them down and said to go down about 500 yards and talk to Sammy Butler since he was the one who took that bridle.

He said, “Just tell ‘im that you want the bridle back and that you have a witness that seen ‘im take it. It’ll scare ‘im enough so he’ll get your bridle for you.”

Chris was a year or two older than me so he did the talkin’. “We want that bridle and we know that you took it. If you don’t give it to me, I’ll get the law after you.”

Well, Sammy went right out and got the bridle and give it to Chris. Then we went back to thank the man. One of us asked him how he done it. He told us that if we wanted to look into the future just to say and do certain things.

One morning I got up and had a feeling that I ought to look into the future to see what was coming. I done everything he told us and words just come into my mind that I was goin’ to fall off my horse and get hurt right bad. I hadn’t ever fallen off my horse. In fact I had him trained. It wasn’t 30 minutes, though, that I went out there and grabbed his mane and went to swing my leg over him. I don’t know what happened but I hit on backwards after swingin’ on the other way. With no mane I just grabbed back and got him by the tail as he took off on a dead run. Pretty quick he met two or three little jumps and with me ridin’ bareback, I fell off and hit right square on my head. I split my head open and about had a concussion. Mother told me that it was black magic and that I better lay off it. I can tell you that I never went through that mumble jumble stuff again.

My Dad worked in the Sugar Factory while we lived in Salem. There was a smart kid that worked in the factory. They was supposed to holler when they was going to roll these big sacks off. The sacks was packed right tight with empty sugar gunny sacks and weighed about 300 pounds. Well, this kid instead of yellin’, why, he rolled one off and then before it hit Dad, he hollered, “Look out below.” Dad just looked up and there it was and he turned to run but it hit him and just smashed his instep breaking 15 or 20 of them little bones in his foot. They took him into the hospital and operated, but he got blood poisoning in it and they had to take his leg off at the thigh. He had this big old heavy leg that weighed about 70 pounds, it felt like. It ain’t’ like they make now. His leg, it’d get sore walking on that. Oh, it’d get red, big red patches where it was. But I tell ya, he’d sit out under that tree and sort tomatoes and cucumbers for hours. Mother pickin’ ‘em out there and us kids helping about a third of what we should have done.

Boy, when we was bad, why, Dad was just as quick as a cat with his hands. He could grab us! You’re cock-eyed right! We would tease cats and were kind of mean and he’d let us know that it wasn’t right. I seen Dad grab Fos one time and had him over his knee and paddled him before Fos could get away. And Fos was grown then, boy, it sure hurt his feelings and he was mad, Fos was. When Dad really whipped us, he used one of them old time straps that he whet his razor on. But, Mother was always too lenient with us. Particularly, me, I was the baby.

After Dad died, Mother had 40 acres she had to use to support us. There was no welfare, widow’s pension, or nothin’. She had to just dig it right out of the garden. That’s what she done, just sold garden produce and stuff. She had three of us underaged children to raise herself and she done it by toil. We lived right there where Fred Sorenson is–that four acres where they got all them homes. Her land was on the curve of the highway going out of Salem. While I was overseas, why, Fos was livin’ in the old house and it burned down. Mother got enough insurance out of it to build a new home. I think it only cost about $750 to build and complete it.

School

There was three of us in school—Lynn Dudley, Norma Peterson, and I on the debate, arithmetic, and spelling teams. We was considered the brightest students and were the three leaders in the classroom. I beat ‘em in math but they beat me in stuff like English and stuff

Linden, he turned out to be the principal of a school and Norma Peterson married a photographer. We were the three that were the leads in the school but I turned out to be pretty dumb. I didn’t finish the 8th grade and never went to school no more or nothin.’

Arithmetic was the big thing for me in school cause I already knew my times tables up to my fives and sixes when I started school. Dad would wake up before daylight and for about an hour he’d teach me times tables. I was just ahead on that arithmetic when I finally started school and I just loved it. But I never had geometry of any of that stuff.

Music, now that’s something I was the dumbest in, what I used to love about Dad, though, why, he could sure sing. I remember that he sung “The Old Armchair” and a half dozen other old songs that were popular at the time. Well, I do not know music at all and I had a teacher that had it in for me and Max Carson and two or three others. We felt like she did anyway. Miss Jones talkin’ to me and Max Carson would say, “Sing louder!” so, boy, I’d blat it out louder and she’d say, “No, that’s worse, that’s worse.” Now she couldn’t tell us what was wrong or how to sing the way she wanted. About this time she’d be so upset that she’d either break a ruler over our hands or make us stand in the corner,’cuz we couldn’t get the right pitch. (I don’t know if she had a dunce cap or not.) Finally she asked,”Well, have you got anyone in your family that knows anything about music?”

I said, ”I don’t know. Dad sings all the time and it sounds good to me.”

I said, “Well, you sing for him and ask what is wrong. I don’t know what’s the matter.”

So we sung to Dad and He said, “Why, what’s the matter with her and her a music teacher! You haven’t got your pitch on your voice is all.”

From then on since I didn’t have no pitch, I’d skip my music lessons and study arithmetic. Fritz is the only one of the bunch that could carry a tune so they said. He got pretty good there for a while.

Dad died in 1926 and we went back to Wyoming. I stayed in Thayne, Wyoming, with Laura and went to school; Mother and Elsie stayed with Beatrice in Afton, Wyoming; and Velma stayed with Clementine in Afton, Wyoming. We came back to Salem before school let out, though, and started back to school just as quick as I got here. By golly, Lester Searles, the principal, said we needed my records but we didn’t bring them with us, ya see. So we wrote Laura and she went down and seen about them. We waited and about a month before school was out, Lester Searles said, “Now if ya don’t get them records I can’t pass ya on to the 9th grade. You’d pass with honors if you just had ‘um.”

My oldest brother that was down there runnin’ horses in Idaho, why, he wrote a letter to Mother and sent a picture of a black horse and a saddle. He told Mother in the letter that if she’d let the baby boy come down and live with him that the horse and saddle was mine. So what did I do. I just kept after Mother. I wanted to be a cowboy. And then I had this excuse, if my records didn’t come to Searles, I wouldn’t graduate from the 8th grade. Besides it would mean one less person for her to support. I kept after her until she finally gave in. I wasn’t at the desert more than two weeks when we heard from Mother. She said that Searles had gotten the records but that I had missed over a month’s school during the year and didn’t have the attendance to pass. So that’s why I didn’t finish school at that time, I just stayed out on the desert and never did go back to school.

In my life time, though, I’ve seen college ones out of work a lot more than I was. I learned to work with my hands and not do anything only the job I was hired out on. Some of them college graduates that was working out to Geneva on that labor gang, couldn’t open them railroad car deals. Fetterman, he had six years (I think he had his Master’s degree.) and hired out there and I’d show him how to dump the ore out of them cars. We had to do them cars and dump the highline as we went along on labor. But he’d keep calling me over and I’d have to crawl over them cars and show him again how to get his side open. Finally he told Roundy that he wasn’t mechanically minded and that he thought that I was getting’ mad. Hell, he quit there and this Roundy got a letter from him. He had a job as assistant to the prosecutor of Los Angeles City. This here was 20 years ago and he was drawing $12,000 a year to start when we was makin’ about four or five thousand over here. But that’s what his education got him. He had all this college deal and he went right in there and got a job makin’ that much money.

Running Horse

I was about 13 when I went to run horses with my brothers. They was down on Jack Creek-Oihec Desert. They was about thirty-five miles from any town right out from Mountain Home in Brune, Idaho. We’d got out there and ketch wild horses for a livin’. They was a bunch of government studs turned loose right after World War I that bred them mustangs till they was polo horses and calvary horses—good horses, though, thoroughbred. We’d go out and make the horses run into one of the traps we’d made. About one out of a hundred we’d sell for $90 and the others we’d get about $10 a piece. After being out on the desert for about six months we’d come in with the shipment and have to drive them to Mountain Home about 55 miles away.

I really missed out on all my young years living out there on the desert like that. Every 1, 1 ½ years I’d get homesick and have to come home to visit Ma. I’d stay a month or two and then on the way back to the desert I’d catch a month or two of spud picking. One time I pretty near joined the CC when they come along. You could always get a job there and I never had anybody in one of them fields pick more potatoes than me if I was usin’ a belt.

The horse we’d catch was black and the biggest, orneriest, trap, spring beauty was a stud. There was horse runners in there for ten years tryin’ to get ‘im. He was about 11 years old and they’d chased him since he was a yearling.

He was such a beautiful thing! Everyone thought he’d weigh about 1100 pounds but he only weighed about 800 pounds when we got him. He was just half as big as he looked but could he dance! He just had springs in his legs. And he was smart and fast; he’d just outrun ‘em all and nobody could get him.

Old Larsen and Whitey was the two best horse runners I every run into in my life. There was only about 6 of us the day we caught the stud: Old Larsen, Whitey, Hap, a couple of other guys, and me. There was spring beauties where this stud and his forty mares were. Old Larsen hid out two or three guys around a pothole (watering hole) with about 50 head of perata (tame horses). Then he and Hap went up and started them off of the butte. About half way down, me and another guy pushed them on down to the pothole. We’d let them drink cuz they couldn’t run so fast when they’re full of water. Just as quick as they got their fill of water out of the pothole, why, then we all just whooshed ‘em right down the canyon. These canyons run right together; they was about half a mile deep with two or three trails across ‘em. At the bottom we had a blind out where we’d made a corral. That’s the way we got ‘im. We had quite a reputation for ketchin’ the wildest stud out there, cuz everyone was after ‘im.

Whitey broke ‘im and give ‘im to his wife. He was small and turned out to be the gentlest. Why, we had horses, ten each, that was a lot better horses than he turned out to be but everybody wanted ‘im. They’d say, “Boy, if we had him we’d give a hundred dollars.” Why, you could buy any good saddle horse broke for thirty dollars and any unbroke for ten dollars. You could have the pick of a hundred head of horses and they was good horses. See this is how they figured. All the horses were good ones and so they went for about a penny a pound or around $10. They figured breaking ‘em and putting ‘em in the bridle was about $20. So $30 was top for a good horse. (The was about the same as the horses people get $300-$400 for now days.)

Down there when we was runnin’ horses, after about six months I’d have about two hundred head. Then them horse runners, they’d get me in a poker game and they’d win me down to about 12 or 15 head instead of the 200. They’d make me quit playin’ poker then, cuz they knew if they won all the horses, I wouldn’t help ‘em drive ‘em into Mountain Home. I was dumb enough to play, but I liked to play cards so good that that’s what they done. My brothers, Whitey and Hap, pretty near won every darn horse there for two or three years.

Out on the desert we couldn’t a went to church if we’d a wanted to. Why all we done was run horses and drink the bootleg made in the moonshine camps right in the canyon there. They give my older brothers ten gallons a month. That was when it was against the law to make it. I was about 14..15. That was them makin’ it at first, course, it turned out toward the end we made it for ourselves.

It was my own fault, I mean, me getting’ out on the desert and getting’ away from Church. I’ll tell you I knew the difference between right and wrong even if I didn’t live it. My folks gave us a good start in life. They seen we went to Sunday School and I knew that I had the Holy Ghost when I left Salem at thirteen. You bet, they taught us what we was supposed to do and let us do it.

When I was about 16 or 17 my brother-in-law, Delbert Heap, told me that his brother who lived in Thayne, Wyoming, would give me a steady job. And he wasn’t kiddin’. We’d get up before daylight about 4 or 5 o’clock and I’d get on my old horse and ride it two or three miles to find the old Holsteins about 17 of ‘em and herd them back to the barn. In the barn we’d put their head in the stanchions and strip them out. They had teats about 1 ½ inches in diameter and we would milk them by hand. By the time we finished milkin’ it would be getting’ light and his wife would have breakfast ready. I could sure eat a lot back then. After breakfast we’d go out and hay all day in the heat but before we could stop for the day we had to do our early morning thing of gathering up the cows and milkin’ them. Then we’d have dinner. I stuck it out from about the 1st of June till the 4th of July when we went to Afton for the rodeo.

I’d been out on the desert about 3 years and was used to riding buckin’ horses. At the rodeo they was hollerin’ for riders so I went out. It cost about a dollar to enter. The first horse I rode didn’t jump hard at all. Then the second one I got on made two jumps and throwed himself off of his feet. I kicked my feet out of the stirrups and jumped clear. When he started to get up, I grabbed the horn and was back on him. I rode him another 6 or 8 jumps.

Boy, you should have heard the officials—were they ever mad! They bawled me out and said I could have been killed, or kicked, and they kept it up till I was about scared. I told them that where I’d come from I’d been riding this way and that you either done that or you walked 20 miles. I’d have sooner taken a chance of getting’ throwed again that I would walkin’! If you lost your saddle out there on the desert and seen a bunch of wild horses, you might not see your saddle for ten days and it’s no fun runnin’ horses bare back.

About that time some other guys came up and one said he was the principal of the high school. He wanted me to play football.

I said, “Why I quit school.”

“Well, I want you to start school again and finish here. How far have you gone?”

“Eighth grade.”

“Eighth grade?”

“Yah, I’ve been out of school two or three years now.”

“Well, where did you learn to ride? Why did you get back on that horse?”

“Well, when I was out on the desert you either got back on a horse or you walked twenty or thirty miles. You know, you had to stay with your horse.”

He said, “By golly, you’re just the material we’re lookin’ for if you’ll come. Do you know anybody around here?”

“Yah, my sisters, Beatrice and Clementine, was both teachers here.”

“You mean Roy Call’s wife? I know them. Why haven’t they had you up here going to school?”

“Well, I’ve been over in Idaho runnin’ horses. I’ll probably stop in Aberdeen, Idaho, to pick potatoes this fall and then I’m goin’ back to the desert.”

“Well, we’ll be able to get you in and get you advanced if you’ll go back to school. You’re just the kind of guy that isn’t scared to get back on somebody and we want you to play football.”

I don’t know whether he could have done it or not. He sure was shocked when I hadn’t finished eighth grade, but he sure wanted me for the Wyoming team. I don’t think I could of run fast enough at least not like my brothers. You take Hap and Whitey. Hap was fast on foot but Whitey would just run circles on Hap or anyone. Fritz was a good athlete and he could out run’em all over here at Spanish on the track team. One day Whitey bet Fritz that he could out run him with a pair of hip boots on. When they went over the line, Fritz was just about one body ahead of Whitey—even after Whitey had stopped. Whitey purtin’ near out run ‘im. He was that fast! That was my oldest brother, that’s sort of Dad’s way. They run about a hundred yards and Fritz got the $5. The way Fritz was built, he’d made a football player if he could of run like Hap or Whitey.

After the deal at the rodeo, I went right back out on the desert and stayed there till I realized it was getting’ a little too rough for me.

When I was about 17 or 18 we took a shipment of horses into Mountain Home and I had $700 for my share. I had a big black horse that I had trained to do anything I told him to do. Well, I was drunk and I rode to the front of the bar. The two front doors were wide open and the thought came to me that I didn’t know if my horse could make it inside. The only way to know anything is to try, so I just stuck him with my spurs a little bit and said, “Duck your head, Blacky, and we’ll go in there and I’ll get me a beer.” So he ducked his head and I rode him in there. We got pretty close to the big, pretty, glass showcase when a bird with a star on him came runnin’ and said, “Get that horse out of here.”

I said, “Just settle down. Don’t spook this horse or everything in here will get busted.”

Instead, the fool just dove for the reins of the horse and Blacky reared up and hit the deputy sheriff with both feet knocking him flat. The old horse was just trembling and I told him to settle down.

I said, “Get me that beer, bartender.”

He said, “You bet.”

He handed me that beer and I had the money in my hand so I threw it on the bar. I took two or three swallows and told Blacky to turn around easy and get us out of there. So he ducked his head and went on out. I went home and in about two hours, here comes the law. I didn’t understand why they were after me ‘cause I was just thirsty. About that time I was almost ready to pass out but they arrested me and locked me up. The next morning they took me up before the judge and he looked me over.

Finally, he said, “What’d you ride into the bar for?”

“I was thirsty.”

He just shook his head and said, “my boy, you were born 30 years too late. You just don’t do those things any more.”

I looked sad and crest fallen and he said, “Do you know what I’m going to do?”

“No, Sir.”

“I’m going to give you a footer out of town.”

I said, “Gee, we still haven’t shipped that load of horses yet and I’ll need to be here for at least another week.”

He said, “Well, that’s all right. But then you get out of town! Don’t you ride into the saloon again!”

After a week I left town, but I didn’t ride into that saloon again. I went out on the desert.

We had a lot of experiences with horses. We rode a lot of ‘em. I helped to break them and a lot of them fell with us or bucked us off.

When I was 17 or 16, I went to work with a Vic Ongre that had Morgan horses. He’d had Carl Ratliffe breakin’ the poor horses but Carl only half broke ‘em. Vic didn’t know that Carl was a rodeo rider and that he was training the horses to buck. I didn’t know it either when I started. I hired out for $50 a month and board-riding roughstring. I rode ‘em all right. One Sorrel would bite and kick at the same time. I’d tie his front legs but I couldn’t get on him that way so then I tied three legs and just looped the other. When I got on him I just let him loose by dropping the rope from his legs. He didn’t jump half as much as the Roan, but I got quite a reputation there for riding that time. I stayed about three months when Vic give me a big old Roan to break. I was out there and I come around one side. The Roan was buckin’ and run right through the bunch of horses scattering ‘em.

Well, old Vic, he got mad and said, “Why didn’t you keep him out of the bunch!”

I said, “I couldn’t do nothin’ with that hammerhead! All I had was a snapper-bit bridle and I couldn’t turn his head either way. He’s so bull headed.”

“I ought to can you!”

“Well, I quit.”

I started to gather my shirts and pants. (Levi’s was all we ever wore with a blue shirt or something. They were just Levi Straus ones that were riveted. The rivets would stick out on both sides and they’d get hot to the touch when you’d get around a fire and them’d burn your butt). Vid came in and told me he really didn’t mean it. That he wanted me to stay and to forget what he had said. I told him that I had quit. It’s a wonder that I wasn’t killed.

There was one time when we was running horses out on Jack Creek and a horse bucked me through a fence and got me all tangled up in the barbed wire. I got on the horse and made about three jumps when he tried loopin’ that round corral where a roll of barbs was along the fence. He got his feet right in the barbs and flopped over. Of course, I jerked loose from him kicking my feet out of the stirrups. When he got up, he took off buckin’ with that big strand of barbed wire wrapped right around his flanks. I had the wire wrapped around me, too. Lucky for me, I had a pair of buckskin gloves on so I could hold onto the wire otherwise it would have sawed my legs right off. I still have a scar on my thigh about 4: long and 2” wide and one on my forearm and hand, too. I didn’t get it sewed or anything. In fact, I didn’t go to the doctor. Florence, Whitey’s wife, stopped the bleeding by putting a sack and a half of flour about 75 pounds on the cuts with dish towels and held it tight.

One time Ralph Pierce and a bunch of us went down on the Snake River. I seen this big hole so I hollered, “Well, I’m going to see how the water is!” I just dropped off from that cliff about 30 feet and dove into the hole but there was a sandbar and the water wasn’t very deep. All of them knew I was dead after droppin’ that far and hittin’ the sandbar. I guess, it just looked like I stopped when I hit. I landed on my chest and the wind was knocked out of me but I was conscious. I couldn’t get my breath or move my arms and I must have floated two or three hundred yards down the river. Pretty soon, I got my breath and was able to keep my nose out of the water. I started to swim and the whirlpools would take me and pull me under so I had to bust loose from them. When I got out I was bleeding where the rocks and sand had embedded in my chest. Grace, Ralph’s wife, picked rocks out for me for some time.

In 1936 I dove in that west portal of Strawberry Reservoir tunnel when the water was full force. Me and Kent Dickerson were coming from Dividend; we’d come off the mine about half looped. Dot and Cy were with us.

I said, ”I wonder how the water is this morning.”

It was so darn cold with 3 inches of snow on the ground that we were all shivering and she said, “You daresn’t try it.”

I said, “The hell I daresn’t!”

I stepped back into a little building and stripped off to my shorts and dove in. It scared me, boy, cause when I hit that cold water, I didn’t really go deep into the water—it was flowing so hard that instead I rode along the top on my stomach and it wasn’t more than 2 seconds for me to get half way to the dam. I was at a point where I could swim and got over to the side. It’s a wonder that I didn’t get cramps, though. When I got out of the water, I just turned blue. Well, here came Cy and, boy, if he didn’t cuss me. He was sure he was going to have to come in after me to save me and that if he had even touched the water that he would have gotten cramps. He couldn’t understand why I hadn’t gotten them. I told him I was too full of that whiskey to even feel the cold. I guess I could never pass up a dare.

My Experiences in the Mines

I’ll tell you that depression wasn’t too bad for me cause I had work as quick as I started the mines. I went up where Hap was working at the Mountain City Copper Mine. They were sinking a shaft and I got a job there. Mountain City is on the Idaho line about 90 miles from Elko just between Elko and where our ranch was. I lived with Hap and his wife, Rosella, who had a big ranch. Once a week we’d ride a horse in to get our mail and we could have the groceries sent out unless we had a big order and then we’d take pack horses either into Bruno about 35 miles away or Mountain City that was about 55 miles. I worked there at mountain City for a year and then I came down and started in the Eureka Standard the Spring of ’32.

My older brothers were good workers and they were already working in the mines when I come looking for a job. It’s quite a story how I got on the Eureka Standard. Cy was the one that talked to the boss, Brandon. There was three or four hundred guys lookin’ for work at the time and Brandon asked Cy if I was as good a worker as him. Cy though that I’d be a better worker since I hadn’t worked in a hot mine before and I’d probably have more wind. Brandon said that he’d hire me then.

Well, I went up there and Brandon hired another guy and I was just standing there. The next day he did the same thing. Each night I’d go home and tell Cy and he’d tell me to stand out where Brandon would know me. I’d been over in front both days so Cy said he’d stay up and point me out to the boss. The next day I was finally hired and went to work for big money. I started at $3.25 a day where I’d been working on them thrashers pitching bundles for a straight 10 hours a day for my dinner and a dollar a day.

The first shift they put me on the trammin’ and they didn’t tell me how much to do. I pushed 33 cars on the 1100 clear back to the “L”. About 3:45 p.m. Old Brandon came in and asked how many cars I’d moved. I told him and he seemed surprised but said, “Okay, that’s fine.” The next day I went ahead and got the same amount. About the third day some of the other miners asked how many I was movin’. When I told them, they warned me that the guys on the other shift were getting’ by with ten or eleven cars and if they found out they were likely to kill me. See, the other shift had the cage riders and the cage riders’d just put this waste in the cars. Then our shift had to push the cars a long way up a steep dirty grade. Here I’d been ridin’ them buckin’ horses and runnin’ horses and for a big husky, stout kid of twenty it was fun to push those cars back and dump them. Those other guys had been working in the mines a long time and were short winded. Well, when they warned me, I cut down to seventeen and I don’t believe I ever went down below fourteen or fifteen cars.

After I cut down Brandon came to me and asked what the matter was.

I said, “Oh, I don’t know. I got kinda tired, I guess.”

“I guess you’ll never make that 33 again, will you?”

“No, I don’t believe so.”

“I wonder what’s the matter.”

“Well, I’ll tell you, I must have pulled my cork.”

(To pull your cork means to wind you. If you run a horse and don’t pull him up you could thump him, or break his wind, and then he wouldn’t be worth a darn after that. It’s an old saying if you pull your cork then you’re likely to kill yourself off.)

He busted out laughin’ and said, “Some other guys got to you, I know.”

We got along fine and they laid off a slug of ‘em up there but instead of laying me off, why, they transferred me over to the Tintic Standard. It was just ‘cause my name was TOLMAN and there’s no doubt about that. We had a name for being good workers. And that helped us all our life to get a job.

My name came in handy down there at the Walker Mine in California, too. That’s just over the line from Reno. You go to Tortolla and then it’s 23 miles into Walker; there’s an aerial tram to Garden City. That’s where all the snow is. I remember when it snowed 11 feet in November and I was snowed in two winters there ’37 and ’38.

Anyway, I went down there rustlin’ a job. There was tree or four Goshen guys there. The first day on the dump they asked for miners so me and Ralph Stone held up our hand. They picked us out and we went to work. A little later the boss came up.

“You know you had guys put in good words for you.”

“We did?”

“Yah, the guys from Goshen recognized Tolman out there.”

So that’s why they give us the job.

The Service

When I was born, I was named Cyril LaVon Tolman. I never liked the Cyril because it sounded too much like cereal to me. LaVon was a girl’s name so I changed my name to Vaughn Cyril Tolman when I got in the service.

I was signed up for the service draft in California, but I went in from Utah. By doing it I saved a guy from Utah from having to go in, but if I’d gone from California, I would have gotten $700 mustering out pay, and as it was, Utah didn’t pay a nickel.

At the time Fos and I were leasing a mine out at Calleo. It was a strip mine just on the Nevada line about 90 miles from Wendover. All its got is a little gas station and to get there you have to take a switchback to the 10,000 foot level.

The draft called me in about four or five times and each time they’d tell me to go back when they found out that I had a lead mine. I was makin’ about $25-$35 a day when wages was $5. I’d just get out there and work about three or four days when another notice from the draft would come. Finally, I got mad the sixth time they called me and I called Cy, who was out here at Alton Tunnel bossin’.

I said, “Cy, if you want that lease of mine, you can have it. But I’m going into the Army. They’ve messed with me long enough.”

He said, “Okay, I’ll quit my job because I want in on that lease.

So I went into the draft office. They started to ask me a bunch of questions and wanted to know where I’d been and stuff.

I said, “Well, you know where I’ve been. You’ve called me in more than five times this last month and you won’t let me work in my lead mine so I want to go into the Army.”

“You know you don’t need to come in.”

“That’s what you keep tellin’ me but I get out there and I work three or four days just to get another letter from you. I have to ride that ore truck each time and I’m sick and tired of it, so I give my lease away.”

They offered to give me a written statement so I could stay out for another six months. I told them to keep the statement since I no longer had the lease.

Boy, you ought to have heard the send off! Mother and one of my brothers was there when I left. I’ll bet it was Cy but somebody was there. Johnny Booth, who runs World Drug in Spanish Fork said, “I wish there was more guys like that fightin’ Tolman. He’ll get his quota of Japs!” There was about two dozen soldiers leaving Spanish Fork the same time that I did.

I was lucky that I hadn’t taken higher math. It’s the reason why my IG was 110 in the Army. We had to take some tests. When the hard higher math questions came up I didn’t know a thing about them so I skipped them. They only gave you a certain period of time to do the 100-200 questions and only counted the number of questions you completed, not the difficulty of the questions you answered. Them college guys got IQ’s of 85-90 cause they’d take and figure them geometry questions out and they’d only get about two-thirds through when the time was up. That was like missing all of the questions. They wanted us to evaluate the situation and decide what we did and didn’t know. They said that anyone that tested over 100 would go into the air corps and anyone with an IQ under 100 would go into the infantry, artillery, or something else. Here they were drafting everyone and me, a miner, and Clint Williams, a sheep herder, were both put into the air corps. They put us in the cock-eyed intelligence and that’s what we done in communications. I asked the General why we were taken over the college graduates and he said the graduates thought that they knew it all, where we could be taught. (I still have my battle stars and all the stuff but I don’t think I deserved them. I wasn’t on the front like them other guys.) We was taking the messages over the teletype and after they taught us, we could do it just as good as them educated guys. We delivered the bomb messages and everything else. We’d know just how many planes we’d shot down just after it happened. We worked in a building where they wouldn’t let anyone that didn’t work there in.

I was in England for two years and I could have gotten an office job but I didn’t care too much for it. Me and Cliff tried to volunteer for the infantry after we got over there. We went and woke up this Colonel Straws and told him.

“We want to go where we can do some good in this war. We ain’t done nothing but sit on a desk.”

“Listen,” he said, “you’ve done just as much good as you would on the front lines. If you think I’m going to let any of my boys go over to the line and get killed, then you guys have another think coming! G’wan back and get in bed and don’t give me any trouble.”

Colonel Straws was over us and we soon really liked him. He was a swell guy. Soon he became a buddy of ours over there and would take us for rides in a plane and everything.

When I was runnin’ horses, them big brothers of mine and them other horse runners took my horses in poker games. I found out that I couldn’t beat ‘em but in the Army it was just like takin’ money from kids to play with them Lieutenants, Captains, and Majors. When I had a good hand, why, they wouldn’t believe it and then when I didn’t, I’d make them think I had a good one by bluffin’ ‘em. I could have had thirty or forty thousand when I came out of the Army if I’d a saved it but I’d just get everybody in town drunk. I’d just throw it away almost. I sent $200-$300 a month home but won $1500-$2000 month after month. I told Mom to buy some more ground or fix up the house with the money I sent but she never spent a nickel of it. She always put the money into savings bonds.

Clint and me went on two volunteer missions. We tried our best to go as tail gunners but we was too tall, you had to be 5’10” or less and the best I could do scrunchin’ down was 5’11” and Clint was an inch taller than that. The tail gunner on the B-24’s was a sittin’ duck for them fighters; they’s always get shot. There was a machine gun in the waist of the plane and we went on both missions as a waist gunner. Our original bomb outfit, the 391st bomb group, had about three fourths of the original crew. They had ten on the crew of each plane.

We got shot at but it was mostly flak; you’d see the little black puffs all around. The whole time you were just hoping they didn’t hit ya. At least we never had any fighters. What little worrying we done it wasn’t about the flak as much as being afraid that another plane would come up and ram our belly while we was flying in the clouds. Unlike the pilots I didn’t understand nothing about the mechanical radar stuff so I did a lot of worrying. There were a lot of other squadrons going at the same time and you could see a bunch and once in a while a cloud would cover ‘em. If ya got mixed up in the clouds, one could hit on your belly and you’d go down. For going’ on these two missions they give us a presidential citation and nine battle stars and we wasn’t in a battle but they give ‘em to everyone in the outfit. Clint and me pretty near got court martialed because they wanted us to wear our medals and we didn’t feel we were entitled to ‘em. I only had two that I felt I deserved. You’d see these infantry guys with arms and legs off and lived steady on them C rations for a year or more when we had about a month on ‘em to show us what they was. Those infantry guys would have two or three stars and they’d been right in the fighting. And here they wanted us to wear nine battle stars and an oak leaf cluster.

While I was in Europe, we did a lot of traveling. We went to Scotland, Manchester and Sheffield. Me and Clint Williams were going to spend a week furlough in Sheffield. We walked from the train down to a pub and my face felt kind of dirty so I touched it with my fingers and they were just black with cinders and stuff from them steel mills. They must have had three hundred smokestacks. It looked like pipes all over. Why, they had them sittin’–rows and rows of them. A bus left town before the train so we took it instead of going back on the train. We ended up in Manchester and spent our week there. We went to Picadilly when they was celebrating, to the Abbey, the castle, and the changing of the guards and stuff. We seen the changing of the guard a half dozen times and enjoyed it more than anything else. Man, that changing of them guards was something. We’d get about half lit and try to get one of them guards to blink, you know, tease them and that. They’d just stand there immobile, though, and you’d never see an eyelash or a muscle move. We’d watch ‘em for hours. They’d be on for four hours and they’d just stand there. I guess if they couldn’t control a muscle they’d be taken off the guard or something. They was the best trained soldiers I ever seen in my life. It was beautiful to watch the changing of the guard.

After the war was over I was ready to leave but my records were fouled up. I had 130 points but my records only showed 110-115 so they were going to put me in the German occupation and that meant I wouldn’t go home for another year and a half. Well, I was mad. I wanted to come home and I knew they was wrong so I’d just take off and be AWOL. They wouldn’t do nothin’ cause they all knowed that they had my records fouled up. There was me and four other guys all in the same spot so we’d take off together. Once I went AWOL for 5 days to go to Little Fos’ funeral, wedding I mean. Well, I felt like it was his funeral when he married that English lady. I was sick! I felt like he was going to his deathbed. He met his Waterloo. She was a good Catholic and them Catholics, boy, they drink for a week at a wedding. Finally, I went back to the base and they said, The Colonel wants to see you, Tolman, for being AWOL again.”

“Okay.” I didn’t go up right then, though, I waited an hour or so.

He said, “You’ve done it again, huh.”

“Yah.”

“Well, I don’t blame you. They’ve got your records fouled up but stick around here.

My orders came in and I was going over for the German occupation. We’d got as far as France when they found my records so I caught a boat to Liverpool and from there sailed home. I was right in the middle of the ocean on my way back to the States when they dropped them bombs on Hiroshima. I went in March of ’42 and I got out in August of ’45.

My Sweethearts

I didn’t ever have very many sweethearts. When I was a young kid about 9, I was a Romeo, though. Why Theora Killian down here, they used to call her “Puppy” so they said it was “Puppy Love” but I didn’t believe it at the time. I went with her from when I was nine till I went to the desert at about the age of 12. When I was 16 I got a letter from her.

She said, “Vaughn, you come home. I want a boyfriend and I want to get married. I want you to come home.”

I wrote back, “I will come back when I get enough money to get married. If you want to go with somebody else and decide to marry go ahead and do it.”

It wasn’t more than a year later that a letter came saying that I hadn’t come back and that she had gotten a boyfriend and was to be married.

One time Kink Hansen was with LaVonna and I was with a Greenhalgh girl out in a boat on Fish Lake. We was drinkin’ beer and about half way out I said, “You put her halfway, Kink, and I’ll bet you a case of beer, I can swim to shore.”

It’s a really cold lake so he said, “I’ll take that.”

I had him tell me when to dive in and what direction was the furthest. He thought the east shore was a little further so I dove in and took off. It was about a mile and a half or two miles and I hurried as fast as I could. I decided when I was about 25 yards from shore to see if I could touch and I couldn’t so I swum a little closer. Then it got shallow all at once and when I stood up and took a step I fell right on my face and pretty near drowned in a foot of water. I didn’t know that I was that tired. What done it, though, was the last hundred yards or so Kink used the motor boat to make waves hoping to make me give up but it only made me mad and I went all the faster. I felt funny falling like that but I won my case of beer.

I had a girl in England that I pretty near married. She was a redhead. We went and seen the Chaplain and he talked us out of it.

He said, “That’s a long ways from home. You get out there in Utah and all it is, is desert.”

She didn’t know what to do then and I told her that if she didn’t know then she hadn’t better take a chance with them deserts but that there were a few green spots in Utah. I’m glad I didn’t get married now.

Me and Clint helped Harry Street who lived on the base with his family of 12 kids by givin’ him some food and stuff. Well, Harry wrote his brother Joe, and told him what we done so Joe invited us to spend a furlough at his home. Charlie Reed wanted to go with us so we told him to write since we couldn’t go for quite a while. Joe said there was room for three so we planned to go. Joe had a little gal about 17 or 18 years old who was the most beautiful gal—well built—I think, I ever seen in my life. This Charlie Reed got away with her and they got married. She was really too young for us since I was 28 and Clint was 29 or 30. Harry was sure disappointed that Clint or me didn’t marry her. Joe really showed us a good time. He took us to the dog races and wouldn’t let us buy a darn thing.

A Couple of Car Crashes

Once I was in a race with a guy from Santaquin to Salem. I had a 1929 Model A and he had a ’32 Chev. I heard them holler “Go!” and I just beat it out of there. I beat two cars that he had to wait for. I didn’t know how far he was back of me but I took that curve goin’ into Spring Lake too fast and the car just rolled over about three times.

I hadn’t let anyone else ride with me and I must have been knocked out. The first thing I remember was someone yelling, “Anybody killed” Are you alive?” There were two couples and one of the girls was Florence Sperry. I couldn’t see anyone cause the glass was shattered and the top was mashed down. The guys got the door off and one of ‘em told me it was about 4 o’clock. I asked the guys to help me turn the car over on its wheels and I got in having to put my head through a hole in the mashed top. I thought that I was heading home but instead headed back to Santaquin so I went back into Walt’s. I got me a gallon of beer and headed to Salem. Come to find out Mel and them thought that I was heading toward Eureka and so they were racing there and never did know I’d tipped over.

In Blackfoot, Idaho, Severin and Velma had a guy, Ted Pollock, workin’ for ‘em. Well, he and I was mixing champagne and whiskey; Ted was drivin’ and we had a couple of girls with us. One of the girls was sittin’ next to Ted and the other one was sittin’ on my lap. While he was drivin’ down the road, Ted reached over and kissed his gal. The car hit a telephone pole and cut it in half. I was as clear headed as would be and knew everything that was happening. When I saw Ted was heading toward the pole, I just took my arm and pulled the girl on my lap behind me. After we were hit, I asked the girl how she was and found we were both ok so I took after the other girl who was runnin’ up the road holding her head and yelling, “Mama, Mama!” Her face and neck was cut and she was bleeding like a stuck hog. I got her back to the car and by then other cars were coming and one stopped and took us to the hospital.

At the hospital I called Fritz and told him that we’d been in a wreck and he said he’d come right down. They took the girl in and I had been sittin’ about 15-20 minutes when a nurse came up and wanted to know if I was hurt ‘cause I had a lot of blood all over. I told her that it was from the girl they were sewing up. She told me to go in and look into the looking glass. Boy, I was just covered with blood and all you could see were the two whites of my eyes. I reached up and touched my hair and my whole scalp just lifted up and when it laid over, it hit my ear on the other side. I left it down and walked out and said, “Yah, I got a little cut here.” About that time Fritz stepped through the door and seeing my scalp like that thought that I was dead. I was as high as a kite but I knew everything that was going on and the look on Fritz’s face started me laughing. He said, “My hell, brother, you’re hurt!” I said, “Nah,” and reached up and flopped my scalp back over. It was a clean scalping like in the Indian days so they just sewed me up. That was Friday night and on Monday I was out thrashing grain; Velma sewed me up a cap so my head wouldn’t get dirty.

My Family

When I met Margaret, she was up there to Dragerton teaching school during the week and then she was over to Winnie’s and that on weekends. The first time she seen me, why, I was so drunk I couldn’t hardly walk and barely remember seein’ her. A couple of days after that Dot started kiddin’ me about Margaret saying that she sure liked me. I wanted to know what she liked about me and all Dot could say was that she just liked me. I decided to make a date with Margaret and convince her that she didn’t like me. I told her that she didn’t want nothin’ to do with me. I liked to drink and gamble and always made the rounds spendin’ lots of money. Here, I knew she was religious and stuff and thought she’d not put up with it. But instead all she did was write her mother and tell her about my drinking and gambling.

The next time I seen her, I brought a fifth with me and started to take it into the house. Margaret hit the ceiling but Grandma Hartvigsen—just like my mother, was so sweet and really stuck up for me too much—went in and got that letter and showed Margaret what she had written. Then Grandma said, “If he wants to bring a drink in the house then he can.” I just wanted to prove that I could if I wanted to, but I didn’t take it into the house.

Me and Margaret was married Christmas Eve in 1945 and about a year later Tom was born. It was a great thing but it scared me when that doctor spanked him. He sure give Tom a couple of hard paddles. I was right there and watched it all. I was holding Margaret’s hand when he was born; he sure was red. We all lived with Grandma and Grandpa Hartvigsen in Santaquin for about six months after that. I was working out to Calleo for about five weeks at a time when I’d come in and celebrate five days and go back out.

I came in from Calleo with a beard I’d been growin’ about five weeks and it was about an inch long. I went to kiss Tom and he looked up and seen that whiskered bird and just busted out screaming. I scared him; I guess he thought a boogerman had him. I went in and shaved it off and then he gave me a big hug, he did. (It sure ticked me when I saw Don with a beard. I said, “Gosh, I didn’t think you’d wear a thing like that.” And he said, “Well, you did and you about scared Tommy to death!” And it did! But it purty near scared me when I seen Don, you know, I hadn’t seen him with a beard before.)

About that time Hap and them were working up Provo Canyon. Jiggs Lofgran, a friend of mine in Salem, was the head of this jackhammer group so I went and seen him. I was havin’ a beer and I seen Jiggs and told him I was lookin’ for a job. He took me to Bill Mason, the superintendent, and I got a job, but Mason said I had to clear it with the Union. I was to start the next day so I made it quick over to the Union Hall. The union guys told me I couldn’t have the job because there were 30 guys ahead of me on the waiting list. Boy, was I mad. Here I had a job, wanted to work but I wasn’t a union member and even if I was they wouldn’t let me keep the job. I stopped into Johnny Booth’s and was tellin’ him about it when he told me he’d see about it. He called the union head and pulled a few little strings. I needed money to join the union and he knew it so he just throwed me forty dollars and told me to pay whenever I could. He knew I’d pay it back when work was good. I went back over to the union hall and as quick as I walked in they asked if I was Mr. Tolman and signed me right up. It was 1949 and we lived right up the Provo Canyon in Wildwood.

There are two things that happened in Wildwood that stand out in my mind. One day John, Hap’s boy, tied his dog to a fence and a rattlesnake came into camp and was heading for the dog. The snake had to go under Tom’s bed to get to the dog. When I seen him, Tom was just getting out of bed with the snake starting under it. I grabbed a new pitchfork that was just outside of the tent and come down on the snake so hard that fork went in three pieces, too. I went over to the office and told Mr. Offutt what happened. When I told him he thanked me and asked me not to tell the people in camp ‘cause they’d all move if they found out that a rattlesnake had been there. He’d had a lot movin’ and didn’t want all of ‘em ta move. He said that I needn’t pay a cent for the pitchfork and that he was just glad I was there and got that snake. I never did have to pay a penny for that fork, either.

It was there at Wildwood that Tom decided that he couldn’t walk. We took him to the doctors but no one could find a thing wrong. I’d a bet my life that he had pains and couldn’t walk the way he acted. He was only just about a year old and had just learned to walk good. He had us pack him up and down that river. Then one day we were on a lake and I heard him say, “Now, let’s see, when I get right over to that big rock my leg will start hurtin’ so they’ll carry me. I guess he’d just do it when he’d get a little tired.

I think we moved to Laura’s in Roy then. I worked there to the Ogden Arsenal. It was up there at Hill Field in that little old cement place.

We had a place down in Salem when Don was born, I think. He was born over in Payson Hospital. They didn’t let me stay in with Margaret. I was in there just before and told that cock-eyed nurse that Margaret was havin’ pains and someone had better get the doctor. The nurse said, “Oh, she ain’t ready yet.” By golly, I’ll tell you, when Dr. Moody came, he was on the run and got there just in the nick of time.

I had a boy and a girl, then a boy, then I missed out on my guess the last time. I bet it was a girl but I couldn’t call the shots and lost ten dollars.

It helped to have been in the Army when I went to hire out to Geneva. Freestone, the personnel manager, looked at my records and said, “Good grief, are you ever the kind of guy we want to hire over here. One that’s been in World War II and went through that many battles.” Why he was dumbfounded.

I said, “Listen, don’t believe all that says.” I didn’t want to say too much ‘cause he might not hire me but I didn’t feel I’d earned all them medals.

He told me, “Well, it’s all right here in black and white.”

I didn’t say no more and Freestone got to be a real buddy of mine. Like the time I asked him and Dale to hire Sherl Ballard out there and they called Sherl up just as quick as I asked ‘em but Sherl had already went to work at Ironton. I worked at Geneva until we went on strike and then I’d go down to the Uranium mine or up in Wyoming on a tunnel.

I remember some of the things the kids did and said. Like the time Tom scattered that soap all around the front room. Them was the best kids to go fishin’ with me, though. I’ll never forget the time Tom and Don was up at Strawberry to the cabin. We’d already give ‘em something to eat so when they got tired they went out to the red panel truck and fell asleep. I’d fished until way late about 9 or 10 and found the kids asleep so I just got in and started home along Sheep Creek. I was drifting down and the first thing I knowed, why, a little voice said, “My gosh, Dad, that’s a skinny road.” That was Don and it really tickled me.

Another time on the way to Strawberry we was goin’ up Sheep Creek about up there where you cross that water and start up the steep deal, when I got a hunch. I stopped and said, “You kids want to see a deer?”

“Yah!”

“Alright, get out of the car then.” So we all got out and I yelled, “Alright

come on out, buck. We’re here and we ain’t got no gun. We won’t hurt ya.” Well, by darn, out came a two point! I was as surprised as the kids when he walked out like that. I said, “Wiggle your ears so you’ll know us next time.” His old ears did flick. My voice must have stung ‘em a little ‘cause he did wiggle his ear. Laugh! The kids really laughed and I couldn’t help but laugh, too! That was the funniest thing you ever seen.

Margaret and me didn’t make it and the divorce was final in 1969. I was retired from Geneva in ’67 and after that I stayed with some of my family and did what I could.

Me and Ett

My brother, Hap, had passed away about three years before and his wife, Ett, was alone so I asked her for a date. We’d only dated three or four times when Ett, Laura, and I went to Wyoming and visited with Myra and Beatrice. At Myra’s, Ernest was trying to talk Ett and me into gettin’ married. He offered his services being the Justice of the Peace. It threw me when he talked that way but, I guess, he might as well have done. Ett and me got married in August of 1971. We had a real nice honeymoon. We went to that lodge up there in Heber. It’s a beautiful place—nice and cool—and we went tramping around through the mountains. Also we went to Strawberry to do some fishin’ and we ended up down to Globe, Arizona, where Ett had her trailer.

We don’t have much excitement down there. We don’t go nowhere only just to church. We’ve never missed a church meeting since we’ve been there. Even the Bishop said, “Brother Tolman, I sure appreciate the work you’ve been doing.” But my gosh, here I’m retired but I’d like some work. I ain’t used to layin’ around.

When the weather’s good we do some fishin’. About two years ago we caught about 18 crappies. They’re better eating than trout when they’re fresh but they aren’t as good frozen so if there are any we don’t eat I make scent for them traps I set out. Them fish make better scent than anything else when they’re rotten. I have a line of traps up to the Indian Reservation in the mountains behind Globe and I’ve done pretty good with ‘em. It keeps me busy since I have to check them traps once a day. After checking my traps a couple of times the brakes on my car went out coming down that steep road. Those were some rides, I’ll tell ya.

I have a green thumb, I guess. I hauled dirt into a garden spot near our trailer last year. Cows eat the cactus and stuff out on the desert so I carried in some cow chips and mixed it in. I grew tomatoes and they had twelve foot vines and lots of tomatoes. Also some volunteer watermelons from the seeds of one we’d had in the spring came up but the fruit didn’t get ripe before it got cold.

My Happiest Time

I had a lot of ‘em but the first thing that came to mind was when I killed that big buck after Glen Schaugard missed him. Glen caught the buck asleep layin’ about 10 feet from him. When Glen saw him he thought the buck was a dead one but decided that he’d put a bullet in him anyway. That buck just jumped up and Glen never got a shot off. He said he couldn’t believe his eyes. I was clear up on the hill about two hundred yards. That buck was at a dead run and his head was right back and as I pulled up I purty near pulled the trigger. If I had I’d a shot three times, maybe, and I’d a had to shoot after he was out of sight. I stopped myself and though, “You’d better let this one shot count or you ain’t goin’ to get nothin’.” So I took a little finer bead with that 25-35 and I just skimmed his rump and hit him right in the neck and he folded. I believe that was the biggest deer I’ve killed. He was a big five point that I got down there at Ubie Dam.

My Most Scary Experience

I was with Lawrence Limb and Marvin South of Dog Valley. Marvin and Lawrence went up one canyon and I went up another one. I saw a three point across the canyon so I shot once and missed and the next time he dropped. I cut across the canyon and came up about 40 yards from him. The deer got up and came right at me. I pulled down and thought that I better get him the first time. I missed. I turned and run, kicked a shell in the gun and swirled around in time to see him standing right up like a billy goat. I shot him right behind the ear. It had long spikes. I’d heard that they charged but that was the first time I’d seen one do it.

My Saddest Times

I’ve really had two sad times in my life. I don’t know which was my greatest sorrow. There was when my Mother died. She talked to me just seconds before she passed away. She said, “If you want me to stay I can probably live, Vaughn, but I feel like I ought to go.”

I said, “Mother, the way you are, I’ll be alright.” Oh, that just tore me apart.

I had the same feeling, though, when we heard Larry had kidney trouble and that it was incurable. About the time Clarence Norman’s kid died at 14 or 15 and knowing it was incurable it would be the same thing with Larry. It was a couple of days after they told us that here come a cock-eyed letter from that Jolley Mortuary. It was just an advertisement, but, oh, that made me mad and bawl. I just felt like they knew about it since Payson Hospital made the report and they sent a funeral arrangement deal so soon after. The doctors said they couldn’t do a thing for him so that’s when we took him to a specialist. Margaret started givin’ him a lot of stuff and changed his diet. I think he almost lived on apple juice for a while. After the doctors said he wouldn’t live, it must have been the stuff Margaret gave him and blessings from the Lord that Larry is still with us.

My Testimony

I’ve learned that it’s important to live what the church teaches. Smoking is one terrible thing for the lungs. When I had that double pneumonia down there in Nevada I tried taking a smoke. Them tubes was plugged up and I’d get air in but I couldn’t get it out. The doctors didn’t say a word about smoking but I learned. When they say that smoking is a matter of life and breath—people better believe it. That’d be one heck of a death. When Fos was in the hospital, Hap said that Fos couldn’t get his breath and they had him under oxygen. He had emphysema and, I think, I’ve got a touch of it, too. They told me over there when they retired me that they had it on my doctor’s report. Smoking is the worst habit and I should a been smarter than to start. I was old enough to know better

Drinking is no good either. It takes a lot of will power to stay away from it. I found that out! My life would’a probably been a lot different if I hadn’t started drinking. It’s harder to stop smoking than drinking, though, at least for me.

I am trying to live differently and do all that I can to help the church. I’ve been helping with the new church building down there near Globe. Course being retired I have a lot of time.

I was able to go through the Arizona Temple for my endowments. I was glad that I could go.

Visit FamilySearch to learn more about Vaughn Cyril Tolman. Visit the Thomas Tolman Family Organization to find out how you can get more involved in family history.